Two World War I Medals of Honor, two names, one New York Marine

A Brooklyn Marine received two Medals of Honor for heroism June 6, 1918, during the historic Battle of Belleau Wood. He also had two names.

That June day, Gunnery Sergeant Charles Hoffman conducted a one-man counterattack against a dozen German soldiers armed with five light machine guns, trying to throw the 5th Marine Regiment off Hill 142 overlooking the wood.

But when he was one of the escorts bringing the Unknown Soldier back from France in 1921 to Arlinginton, he was Gunnery Sgt. Ernest Janson.

Janson was already a veteran before World War I, having served 10 years in the U.S. Army before he enlisted in the Marine Corps in June 1910. He was promoted to corporal less than a year later and made sergeant in August 1914, serving aboard a variety of navy ships up until 1916.

At some point, and for reasons nobody seems to know 100 years later, his enlistment in the Marines was as Charles Hoffman.

There are no records or mention of Janson’s motivation for serving as Hoffman during the war.

Following the World War he changed his name to Janson, which apparently was his real name, although the official Medal of Honor Society website records his Medal of Honor as being awarded to Charles Hoffman, not Ernest Janson.

The two Medals of Honor for the same action are easier to explain.

In 1918, the 5th Marine Regiment was fighting as part of the Army’s 2nd Division. Hoffman/Janson got one from the Army because he served in an Army division and one from the Navy, because the Marines are a part of the Navy. This was not that unusual in World War I. The Army and Navy were both allowed to recommend members to receive the Medal of Honor.

Five other Marines would be double recipients-getting a medal from the Army and a medal from the Navy-for the same actions in the same battle.

The rules were changed after the war, so that has never happened since. A new standard was established by the Medal of Honor review board to require only one medal could be awarded for a single action.

At Belleau Wood, Janson, 39, was one of the company’s oldest and most experienced Marines when the unit moved into the line for combat in the spring of 1918.

The Germans were pushing toward Paris again in the Second Battle of the Marne. American Commander General John J. Pershing decided to commit American divisions under French command to stop the attack.

One of those divisions was the 2nd, which included a brigade of soldiers and one brigade of Marines.

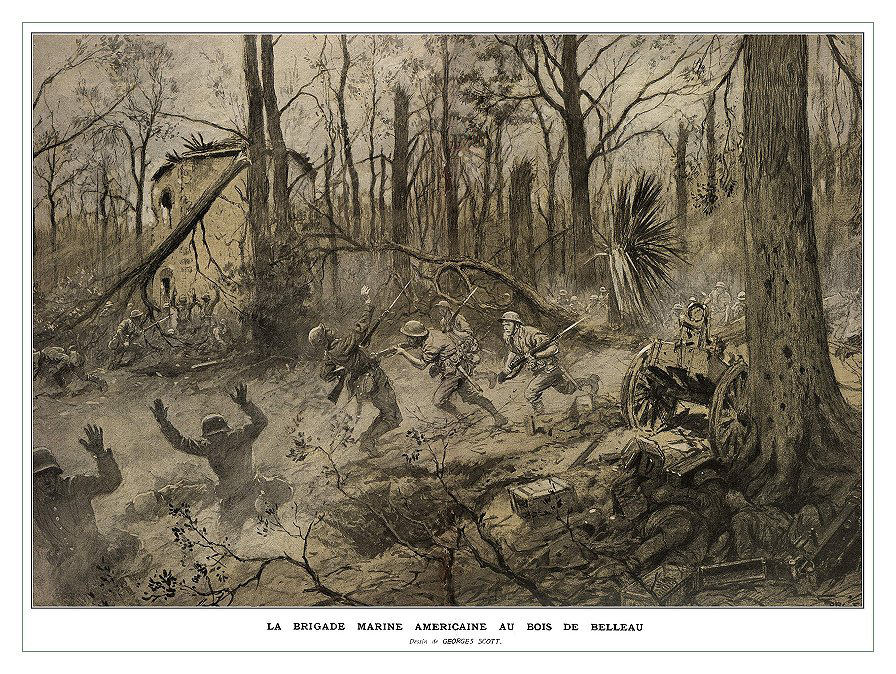

The Battle of Belleau Wood marked a turning of the tide in June 1918.

The arrival of the 2nd Division, with its two Marine regiments, stopped the final German offensive of the war June 1, 1918, some 30 miles from Paris. By June 5, the Marines were ordered to the offensive to clear Belleau Wood of German forces.

On June 6, the attack kicked off. The day would be one of the bloodiest in Marine Corps history. The Marine regiments suffered 1,087 killed or wounded on the first full day of the battle of Belleau Wood.

Janson’s company reached its objective near Belleau Wood on a terrain feature known as Hill 142.

Only two of the five Marine companies had been present at the start of the attack and two more Marine companies would arrive just in time to provide the manpower to hold their position.

Janson, while hastily organizing his defense on the objective, saw a dozen enemy soldiers armed with light machine guns approaching his unit position.

Janson gave the alarm to his Marines and rushed to stem the counterattack, bayoneting two enemy soldiers and forcing the remainder to flee the scene.

“His quick action, initiative and courage drove the enemy from a position from which they could have swept the hill with machinegun fire and forced the withdrawal of our troops,” noted his medal citation.

Janson’s Medal of Honor would be the first among the American Expeditionary Forces.

In November 1918, Gunnery Sgt. Hoffman returned to the United States and was admitted to the Naval Hospital in New York, for continued treatment of wounds received in action back in June.

He also dropped his assumed name and returned to Ernest Janson by 1921.

As a serving Medal of Honor recipient, Janson was selected to represent the Marine Corps service as a pallbearer for the November 11, 1921, internment of the World War I Unknown Soldier, joining two Navy petty officers and five Army noncommissioned officers.

Janson continued his Marine Corps service as a recruiter in New York City up until the summer of 1926 when, at 48, he was transferred to the Marine Barracks at Quantico, Va. Promoted to sergeant major that fall, Janson retired and returned to New York.

Sgt. Major Janson died on Long Island after an illness in May 1930 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Brooklyn.

His gravestone has Ernest August Janson on top, but the final line reads “AKA (Also Known As) Charles E. Hoffman.

During the World War I centennial observance, the Division of Military and Naval Affairs will issue press releases noting key dates that impacted New Yorkers based on information provided by the New York State Military Museum in Saratoga Springs. More than 400,000 New Yorkers served in the military during World War I, more than any other state.